Across the United States, November is synonymous with preparations for Thanksgiving. Classrooms and public areas are decorated with warm-, earthy-toned cutouts of turkeys; English settlers – the Pilgrims, as they are known – who made a new home in a country new to them; and “Indians” with colourful feather headdresses and vests made of construction paper.

Families come together from all over the country for a feast. And some arguments.

- list 1 of 3Did Trump spend 2017 Thanksgiving with Epstein?

- list 2 of 3‘Gobble and Waddle’: Trump pardons Thanksgiving turkeys, blasts Democrats

- list 3 of 3Could Trump’s plan for Alcatraz end this Indigenous Thanksgiving tradition?

end of list

America’s pop culture dominance has meant that songs and movies have introduced these cultural staples to the rest of the world, even among those who don’t celebrate Thanksgiving or fully understand it.

But to millions of Indigenous Americans, the story of Thanksgiving is also closely intertwined with their history of invasion, occupation, displacement, death and devastation that their communities faced as waves of settlers arrived and took over what is today the US.

![Reenactment scene of the first Thanksgiving Dinner in Plymouth in 1621 with a Pilgrim family and a Wampanoag Indian {Shutterstock]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/shutterstock_60321184-1764251571.jpg?w=770&resize=770%2C532&quality=80)

Here’s a look at what the historical journey of the US has meant to its Native American communities through maps showing where they once lived, how they had to move and the reservations they are now largely ghettoised in.

When did Thanksgiving become a national holiday?

In 1863, a proclamation by President Abraham Lincoln turned the last Thursday of every November into a national holiday for giving thanks.

This occurred in the middle of the Civil War in the United States between the Union, or northern part of the country, against the Confederacy, the southern states that wanted to preserve a system of slavery. The Civil War spanned from 1861 to 1865, and nearly 700,000 soldiers were killed.

Advertisement

The proclamation for the national holiday came about after a campaign led by Sarah Hale, a poet, editor and activist, that began in 1846. She’s most commonly known as the author of Mary Had a Little Lamb.

But long before Lincoln’s proclamation or even Hale’s campaign, the tradition that was formalised as Thanksgiving was common in the original settler communities of New England.

When and where was the first Thanksgiving?

In 1606, England’s King James I divided the east coast of what is now the US into the London Company, which later became the Virginia Company of London, and the Plymouth Company. Both were joint-stock trading companies, much like the British East India Company, which was set up in India in 1608.

This was still more than a century and a half before the US was born.

The goals of these British trading companies were to find gold, search for trade routes and compete with other European powers.

The first settlement by the English in the New World was in 1607 when the Jamestown colony was established on the banks of the James River in present day Virginia. This was the ancestral home of the Powhatan Indigenous people.

In 1619, the first recorded African slaves were brought to the colony to work in the profitable tobacco fields.

Jamestown as a colony was ravaged by famine, disease and resistance from Indigenous communities.

On November 11, 1620, a group of 102 English families, known as the Pilgrims, reached present-day Provincetown Harbor, Massachusetts, before anchoring their ship, the Mayflower, in present-day Plymouth Harbour on December 16. The colonists named it New Plymouth, which was the home of the Wampanoag people.

But nearly half of the Mayflower’s passengers died in that first winter as New Plymouth was racked by disease.

At the same time, the colonists learned survival skills, including farming on land that was foreign to them, from some of the Indigenous communities.

It was in October or November 1621 that the seeds of Thanksgiving were laid with a feast among the surviving Pilgrims and the Indigenous people who surrounded their colony.

But in 1622, a vessel called the Sparrow brought the beginnings of another settlement, and two other ships followed soon after. Altercations between the colonists and Indigenous people grew. Ultimately, the Native people fled, and the trade ecosystem that the Plymouth Colony had set up with the Indigenous communities broke down.

Advertisement

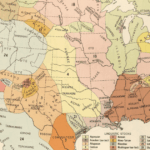

1763 – proclamation by the king

Under the Royal Proclamation of 1763, Great Britain set aside resources for the Native people. Shown on the map are British colonies, Crown lands reserved for Indigenous communities, and Spanish- and French-held areas. This is recorded as showing the movement of Indigenous people from the coast to inland areas.

1776 – US independence

In an act of defiance against the Crown, the original 13 settler colonies declared independence in 1776 during the 1775-1783 Revolutionary War.

1806 – Thomas Jefferson’s letter to the Mandan Nation

Meriwether Lewis of Virginia and William Clark of Kentucky led the first US expedition westwards (1804-1806), charting a route to the Pacific and opening the path for the US expansion.

Along the way, they met with the Mandan Nation along the Missouri River.

The third president of the US, Thomas Jefferson, saw the importance of having them as partners for trade and intelligence in the west.

Jefferson’s 1806 message to the Mandan Nation encapsulates the early US policy of Native assimilation. In the letter, Jefferson welcomed Mandan leaders to Washington, DC, and outlined a paternalistic vision in which Indigenous peoples would “mix with us by marriage”, eventually becoming absorbed into the expanding US.

Historians see this as a blueprint for the federal “civilisation” programme that became the effort to replace Indigenous sovereignty with American identity through trade dependency, intermarriage and cultural transformation.

1830 – Indian Removal Act

Half a century after the birth of the US, the Indian Removal Act of 1830, signed by President Andrew Jackson, authorised the federal government to negotiate treaties with Indigenous communities.

Land was identified west of the Mississippi River for communities that had been displaced from elsewhere. This resulted in the forced migration of Indigenous people from the East Coast inland and in some cases all the way to the present-day Midwest.

The forced displacement of five Indigenous peoples from the southeastern US to what is today Oklahoma is called the Trail of Tears because of its high death toll. Nearly 60,000 people were forced to move overland without much say about their own destiny. Between 10,000 and 15,000 people died along the way.

Among the people caught up in these forced removals were the ancestors of Rene Locklere’s community, the Lumbee Nation from North Carolina.

Her tribe has been recognised by the state since 1885 but is not federally recognised. Native American tribes that are recognised have certain rights of self-government, are considered dependent nations within the US, and are eligible for federal subsidies and grants to fund healthcare, education, housing and infrastructure.

Locklere, 60, is a former US Air Force lieutenant colonel who lives in Virginia and maintains a home in her ancestral lands in North Carolina. She worked for the armed forces for nearly 20 years, and after she retired, she began a journey to get her tribe recognised by federal authorities.

Advertisement

“I took my combat boots off and put my moccasins back on to try to help our people as much as I can,” Locklear says.

Her tribe is almost 60,000 people strong, and she has been recently to Capitol Hill with help from North Carolina Senator Thom Tillis to fight for her tribe’s chance for federal recognition. The Lumbee Fairness Act, which would grant the Lumbee full federal recognition, passed the House of Representatives in December but is awaiting Senate and presidential approval.

“It’s not because of charity. It’s not. It’s not because we’re standing in line for a handout or anything like that. It was a part of a larger policy and a requirement of a government-to-government relationship with Indigenous people,” Locklear says.

1849 – Gold Rush

On the West Coast in present-day California, which was still part of Mexico at the time, gold was discovered in January 1848, and the following month, the US government signed the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, making it part of US territory.

The rush of people migrating to California in 1848 onwards was called the Gold Rush. Hundreds of thousands of people moved into the area, where Indigenous tribes and nations were already living.

Charlene Njemeh, 53, is the chief of her tribe, the Mukame Ohlane, who trace their origins back to what is now Silicon Valley. Her ancestors lived during the influx of new residents during the Gold Rush.

Njemah says the original land of her nation is spread over five counties in present-day California. They are one of the many unrecognised tribes in the United States. Her mother was the chief before her.

“Our tribe has always been in a fight and a struggle to get a relationship with the government because that’s what federal recognition is. It’s a government-to-government relationship.”

The Mukame Ohalane people, like many other tribal nations, were forcibly pushed into the mission system, in which Catholic missions tried to convert them to Christianity.

1851 – Indian Appropriations Act

The 1851 Indian Appropriations Act marked a major turning point in US policy by creating the reservation system, which confined Indigenous nations to fixed parcels of land controlled by the federal government.

It ended the recognition of tribes as sovereign nations and paved the way for forced relocations, broken treaties and tighter military oversight. The act laid the groundwork for decades of displacement as tribes were pushed onto smaller, unfamiliar territories while white settlements rapidly expanded across the continent.

Aaron Carpella, a 45-year-old member of the Cherokee community married to a Choctaw Nation member, lives in eastern Oklahoma in the tribal territory where his ancestors were forcibly relocated due to the Indian Removal Act. He is a former activist and now runs Tribal Nations Maps, which creates maps tracking the journey of Indigenous people through US history.

Carpella says nearly 20 percent of Oklahoma residents are Native people, and much like his family, many residents can trace their lineage back to the time of relocation.

When tribal territories were created in exchange for Native Americans’ land they had lost, their new land was supposed to be theirs in perpetuity, passed down from generation to generation. But the government instead carved up the new Native homelands into smaller, fixed allotments under federal oversight.

Advertisement

As their descendants grew, the size of individual land holdings shrank. “So there’s a lot of Natives here that have like a half an acre [2,023sq metres] left or a quarter of an acre [1,011sq metres] or they’ve lost all their land,” Carpella explains.

1939 – impact of Indian Reorganization Act

By 1939, the US was deep into implementing the Indian Reorganization Act, a policy meant to reverse decades of forced assimilation and land loss.

Tribes were drafting new constitutions, restoring forms of self-government and trying to reclaim lands.

Federal agencies reshaped how reservation resources were managed, marking a slow shift away from allotment and towards stronger, though still limited, tribal sovereignty.

But the policy has consistently clashed with reality. Oklahoma, where Carpella lives, is a case in point.

A 2020 Supreme Court ruling declared a large portion of eastern Oklahoma as “Indian” country.

“But 80 percent of the people who live here are not Native and they live within cities, so it’s like this overlapping concept of municipalities on top of sovereign nations. And so you have regular police officers and then you have tribal police officers and then you have Bureau of Indian Affairs police officers,” he explained.

The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) is the US federal agency responsible for managing relations with American Indian and Alaska Native tribes, overseeing land, services and treaty obligations. It is housed within the Department of the Interior in Washington, DC, and led by a presidentially appointed director. Many employees in the BIA are Natives, especially for tribal liaison, education and culture programmes.

As a result, Carpella says, there is a constant battle over jurisdiction. “Our cars have tribal plates, so police don’t want to stop us because we have a Native American licence plate,” he explains. If they are stopped, they have to call the tribal police, starting a time-consuming exercise.

“In our treaties, it says that Native people can hunt whenever we want wherever we want in Oklahoma in perpetuity without government intervening, but what happens is the state government will send out its wildlife officers to give tickets to individual citizens that are just out there hunting deer for their family,” he says.

Native Americans today

Carpella has spent the past 15 years putting together a map based on Native peoples’ voices and memories passed down from generation to generation about where their people came from and what languages they spoke.

This open source map is unique in the US. Carpella uses this map to do workshops in educational institutes to spread awareness. He copyrighted his map in 2012.

“I used to be an activist. I felt like I was outside of the fence, like shaking the fence trying to change at a city council meeting or at a school, trying to get them to change a racist mascot or something. And now I have these products that are in the schools changing minds,” Carpella says.

“It’s really good to see that there’s a growing awareness. I think 20 years ago, half of Americans didn’t even know that Native Americans still existed,” he says, citing polls that indicated at the time that about half of Americans thought Indigenous Americans were ”all gone”.

According to the 2020 US census, 9.6 million people in the US identify as having Native American heritage, which is an 85 percent increase from 2010. The growth is mainly attributed to how data are collected.

The blood quantum policy, created by the US government in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, defined Native identity by calculating the fraction of “Indian blood” a person carried, often requiring at least one quarter to qualify. Many tribes say it is a colonial system that divides families and threatens the long-term survival of Native nations.

According to Locklear, there is no universal meaning of the word “Indian” in the United States.

“If both parents are Native, the child is considered 100 percent [Native],” he says. “If mixed-race parents, the child would be half, three-quarters, one-eighth or something like that.”

“Over time, blood quantum was a genocidal policy because it helps limit membership or citizenship over time,” Locklear says. “One of our sovereign powers is to decide who can be a Lumbee citizen. I think this right is essential to our ability to self-govern.”

British Caribbean News